Are you SURE about your Diagnosis?

This Case of the Month deals with a case in a 67 year old gentleman I saw 25 years ago. Although the case was completed so long ago, the implications of the case stay with me to this day.

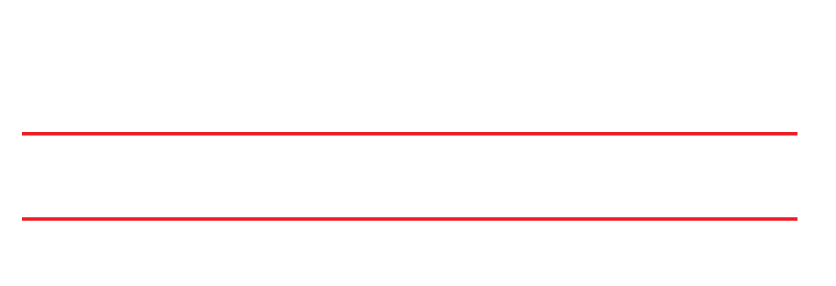

The case had already been started in the referral’s office. The patient had complained of a localized fluctuant, soft swelling in the buccal sulcus area of the maxillary right premolars and first molar. The first premolar had been previously accessed by the referral under local anesthesia and the referral said that he was having difficulty locating the apices because of the small canals. He asked me to complete endodontics on this premolar. (We did not have a cbCT in our office back then)

Upon his arrival I noted the patient had a small bit of extraoral swelling but certainly nothing more than would be expected with a nonvital tooth with acute periapical periodontitis. Intraoral swelling was confirmed. Percussion and periodontal findings were within normal range for the entire quadrant. However, something in the dental history did not make sense.

Closer examination of the first premolar showed no evidence of prior restoration (other than the access temp), This tooth was virgin prior to access. Transillumination showed no evidence of fracture. Yet there was a large radiolucency and associated swelling in the area. Why? Was this tooth originally non-vital and causing the swelling? How could I tell?

To be sure, I pulp tested both the second premolar and first molar again with cold tests. They both responded vital. The cuspid tested poorly with thermal tests so I did a cavity test and actually made a pinpoint exposure before arriving at a positive vitality test. The exposure was sealed with MTA and the cuspid access was restored with composite. All three of these teeth were responsive – they could NOT be the source of the lesion.

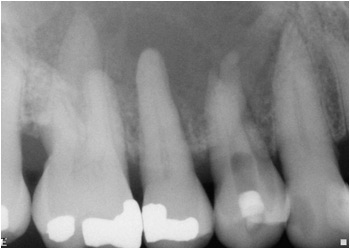

I then placed a rubber dam and made further access into the tooth with small working length files. I was able to obtain apical patency but as I did the patient did note sharp sensations in both canals as I approached the apex. This indicated to me that BOTH canals were vital. This was NOT consistent with an endodontic etiology for the radiolucency and swelling.

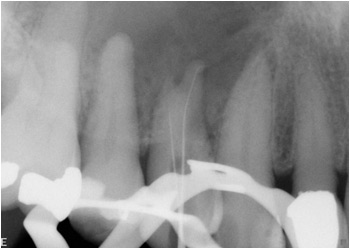

The case was completed as usual after having anesthetized the patient but I was concerned.

After completing the endodontics, I removed the rubber dam and attempted an incision and drainage procedure in the most fluctuant are of the swelling. Much to my surprise and dismay, there was no drainage at all, even after blunt probing the incision. I became very concerned.

After completing the endodontics, I removed the rubber dam and attempted an incision and drainage procedure in the most fluctuant are of the swelling. Much to my surprise and dismay, there was no drainage at all, even after blunt probing the incision. I became very concerned.

I told the patient that it was my opinion that the swelling was not caused by an endodontic problem and I strongly suggested that he be referred to an Oral Surgeon for further evaluation and likely biopsy. The patient seemed unimpressed by my diagnosis. I immediately phoned the referral to tell him that I had a “funny feeling” about this case. My intuition and experience told me that there was more here than was originally diagnosed. I insisted that he speak to the patient and make sure that he kept the appointment that my staff had scheduled for him with the Oral Surgeon.

The report was as follows:

Biopsy Specimen: Two irregularly shaped irregularly pigmented pieces of tissue – one 1.3 x .9 x .5 cm, the other 1 x .7 x.4 cm

Microscopic evaluation: The specimen in its entirety consists of malignant lymphoid tissue. histologically, the lymphoid cells are two to three times the size of normal lymphocytes with somewhat vesicular nuclei. Appreciable numbers of mitotic figures are noted within the lesion.

Diagnosis: Malignant Lymphoma, Diffuse, large cell type of tissues from the maxilla. PATIENT REFERRED IMMEDIATELY TO AN ONCOLOGIST FOR RECOMMENDATIONS AND TREATMENT.

Conclusion

In a busy office with high overheads and constant financial pressures, it is very tempting to make a quick diagnosis and access a tooth in an attempt to treat what may initially seem to be endodontically related symptoms. BUT that does NOT relieve us from performing the proper diagnostic tests.

When patients are symptomatic, we MUST reproduce the patient’s symptoms in the chair for proper diagnosis. In some cases, in order to determine vitality, that means a cavity test. Practitioners must be able to substantiate treatment with science, rather than simply an impression, radiographic appearance or that it “looks” obvious.

In this case, attempting access in an anesthetized virgin tooth suspected to be necrotic (and the source of the lesion) but not confirmed – lead to misdiagnosis. In most cases it merely means that another tooth is involved and that too ends up being treated. However, in rare cases like this one, malignancies can be missed. We must always remember that although such lesions are rare, the consequences of not considering them can be catastrophic. The Oral Surgeon said that in this case, while the situation appears NOT to be immediately life threatening -it certainly warrants serious concern and immediate aggressive medical treatment.